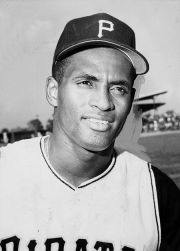

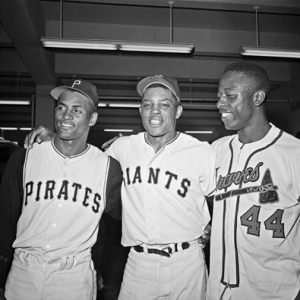

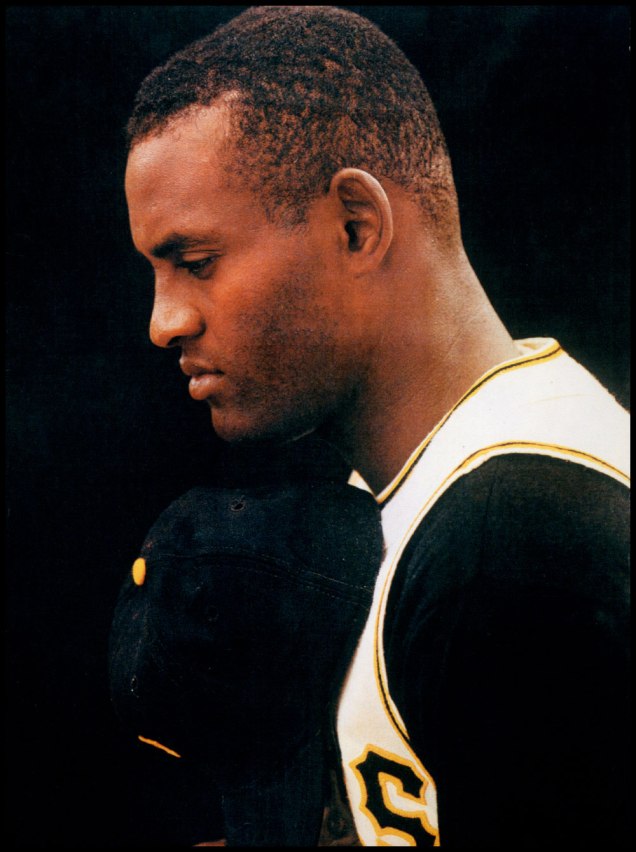

Prior to the start of the 1970 MLB season, Pittsburgh Pirates general manager Joe L. Brown was looking to trade for some pitchers to enhance his team’s chances for a World Series title. He approached Roberto Clemente and asked “The Great One” who he should go after. The Latin American hero from Puerto Rico responded, ” Get the little Italiano from St. Louis. If Giusti is sound, then he can help the Pirates. He has always had good stuff, and he is a tough competitor.” On October 21, 1969, Joe L. Brown made a trade with the St. Louis Cardinals to bring Dave Giusti to Pittsburgh. In an interview with the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette in 2002, Dave Giusti said , “I did okay against Clemente, and that’s one of the reasons I ended up with the Pirates.”

Prior to the start of the 1970 MLB season, Pittsburgh Pirates general manager Joe L. Brown was looking to trade for some pitchers to enhance his team’s chances for a World Series title. He approached Roberto Clemente and asked “The Great One” who he should go after. The Latin American hero from Puerto Rico responded, ” Get the little Italiano from St. Louis. If Giusti is sound, then he can help the Pirates. He has always had good stuff, and he is a tough competitor.” On October 21, 1969, Joe L. Brown made a trade with the St. Louis Cardinals to bring Dave Giusti to Pittsburgh. In an interview with the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette in 2002, Dave Giusti said , “I did okay against Clemente, and that’s one of the reasons I ended up with the Pirates.”

The oldest of two sons born to David and Mary Giusti on November 27, 1939 in Seneca Falls, New York, Dave Giusti‘s first word out his mouth was reportedly “ball”. With a father who played semi-pro baseball before his birth and an uncle who was the captain of the Syracuse University baseball team in 1957, Dave Giusti had athleticism in his DNA from an early age. He followed in his uncle’s footsteps to become the captain of the Syracuse University Orangemen in 1961, when the baseball squad went on to the College World Series but came home empty-handed.

The Houston Colt .45s, a National League expansion team, signed Dave Giusti as an amateur free agent shortly after college graduation on June 16, 1961. He used part of the $35,000 signing bonus to pay off his parents’ medical bills and purchase an insurance policy. The promising MLB prospect simultaneously pursued a high school science teaching career while earning a master’s degree in physical education during the off-season.

The Houston Colt .45s, a National League expansion team, signed Dave Giusti as an amateur free agent shortly after college graduation on June 16, 1961. He used part of the $35,000 signing bonus to pay off his parents’ medical bills and purchase an insurance policy. The promising MLB prospect simultaneously pursued a high school science teaching career while earning a master’s degree in physical education during the off-season.

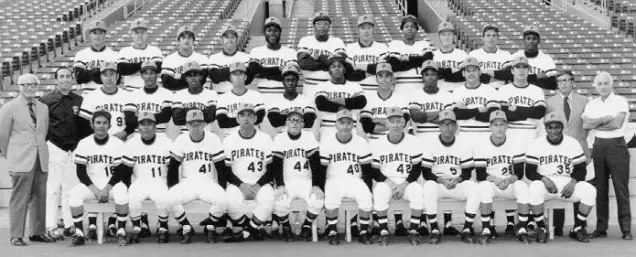

Dave Giusti made his MLB debut on April 13, 1962. He remained with the Houston organization through 1968 and played for the St. Louis Cardinals in 1969. Prior to being traded to the Pittsburgh Pirates, Dave Giusti was used as a starting pitcher. Bucs manager Danny Murtaugh converted him to a reliever. Assuming a new role as the club’s elite closer in 1970, Dave Giusti put together a 9-3 record with a 3.06 ERA and 26 saves.

During the 1971 regular season, Dave Giusti helped the Pittsburgh Pirates during the 1971 regular season by leading the National League with 30 saves and posting an impressive 2.93 ERA. He was also instrumental in the 1971 National League Championship Series when he became the first MLB player to pitch in every game. In four scoreless appearances and 5.1 innings pitched, Dave Giusti gave up just one hit with two walks and three strikeouts. He later led the Pittsburgh Pirates to the franchise’s fourth World Series Championship title (1909, 1925, 1960, and 1971) after appearing in three 1971 World Series games and picking up one save. Dave Giusti achieved major career milestones including playing in his first MLB All-Star game and being named Sporting News National League Fireman of the Year in 1971. He became even more dominant in 1972 when his ERA dropped one point to a minuscule 1.93 and he tallied 22 saves.

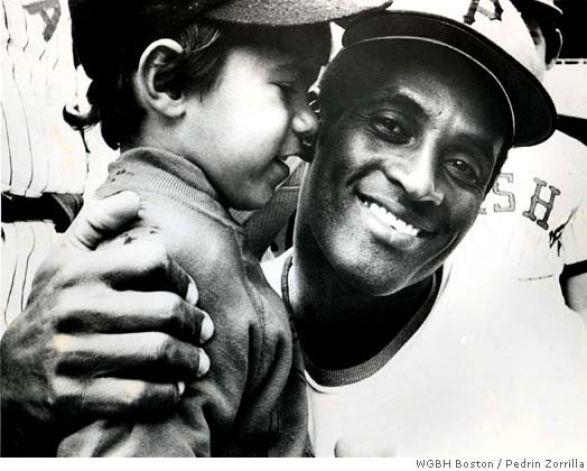

The next season proved to be traumatic following the loss of teammate Roberto Clemente, who died a martyr after losing his life aboard an ill-fated aircraft full of supplies destined for earthquake victims in Nicaragua on December 31, 1972. The Pirates dedicated the 1973 season to the legendary humanitarian and player. Despite not having Roberto Clemente in the lineup and in right field, 1973 National League All-Star Dave Giusti put together a 9-2 record with a 2.37 ERA and 20 saves. Readers wanting to learn more about the late and great Roberto Clemente should check out Roberto Clemente facts most don’t know: Part 1-U.S. Marine Corps Reserve Roberto Clemente and Roberto Clemente facts most don’t know: Part 2-Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Vic Power.

The next season proved to be traumatic following the loss of teammate Roberto Clemente, who died a martyr after losing his life aboard an ill-fated aircraft full of supplies destined for earthquake victims in Nicaragua on December 31, 1972. The Pirates dedicated the 1973 season to the legendary humanitarian and player. Despite not having Roberto Clemente in the lineup and in right field, 1973 National League All-Star Dave Giusti put together a 9-2 record with a 2.37 ERA and 20 saves. Readers wanting to learn more about the late and great Roberto Clemente should check out Roberto Clemente facts most don’t know: Part 1-U.S. Marine Corps Reserve Roberto Clemente and Roberto Clemente facts most don’t know: Part 2-Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Vic Power.

In 1974 Dave Giusti became the first relief pitcher in MLB to earn a $100,000 a year when he delivered 12 saves and a 3.32 ERA in over 105 innings pitched. After returning from elbow surgery, the dominant Pirates closer saved 17 games with a 2.95 ERA in 1975. The following year sportswriter Harry Stein named Dave Giusti as the relief pitcher on his all-Italian team in an Esquire magazine article. He was 47-28 with a 2.94 ERA and 133 saves in his seven years as a member of the Pittsburgh Pirates. Dave Giusti was traded to the Oakland Athletics in 1977 when he went 3-3 with a 2.98 ERA and six saves in 40 games before being dealt to the Chicago Cubs late in the season. The proud Italian American finished his 15-year career in 1977 with a 100-93 record, 145 saves, and a 3.60 ERA. The closer with impeccable command threw a total of 335 ninth innings during his career and set the MLB record for most ninth innings pitched without hitting a batter.

Dave Giusti was inducted into the Pittsburgh Chapter of the National Italian American Sports Hall of Fame in 1987. He was also the first Italian American baseball player inducted into the Greater Syracuse Sports Hall of Fame (GSSHF) in 1989. Since then fellow MLB veterans Jason Grilli (2019), Armond Magnarelli (2004), Frank DiPino (2000), Luke LaPorta (1991), and Anthony Simone (1991) have joined Dave Giusti in the GSSHF.